As animals ourselves, we think we see happiness in our fellow creatures all the time. Dogs romp in the park; squirrels chase each other up and down tree trunks; Tango purrs his head off at night while attempting to sleep on my face. Yet I know that it may not be glee because I can’t be certain what emotions are felt by a creature that can’t speak to me. Misinterpretation is possible. Sure, young squirrels could be playing, but adults are more likely to be chasing off a rival for their stored acorns or competing for a potential mate.

For decades, scientists have struggled to identify or measure true joy — or “positive affect,” in sci-speak — in nonhuman animals, even though they’ve long assumed it exists. In the late 19th century, Charles Darwin wrote, “The lower animals, like man, manifestly feel pleasure and pain, happiness, and misery.”

But in the 20th century, psychologists focused on strict behaviorism, which limited scientific study to actions that could be objectively tallied. Think Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov and the dogs he conditioned to expect food when he rang a bell, giving him a measurable drooling response. Or American psychologist B.F. Skinner, who put rats and pigeons in “Skinner boxes” where they were trained to push levers and peck keys for rewards. That history left scientists wary of anthropomorphism and subjective topics like feelings.

That’s true for positive feelings, at least — there has been loads of scientific attention on misery. In part, that’s because researchers aimed to understand and relieve suffering, not just in animals but in people experiencing pain, depression or other clinical problems. It’s also straightforward to measure a negative response, such as freezing in fear, compared to subtler signs of contentment.

All this history made the study of animal feelings largely taboo, a trend bucked on occasion by researchers like the late Jaak Panksepp, an Estonian neuroscientist and early leader in the study of emotions in the brain. In the early 2000s, when Panksepp reported that rats make a laughter-like sound when tickled, scientists were doubtful; the ultrasonic calls are inaudible to human ears.

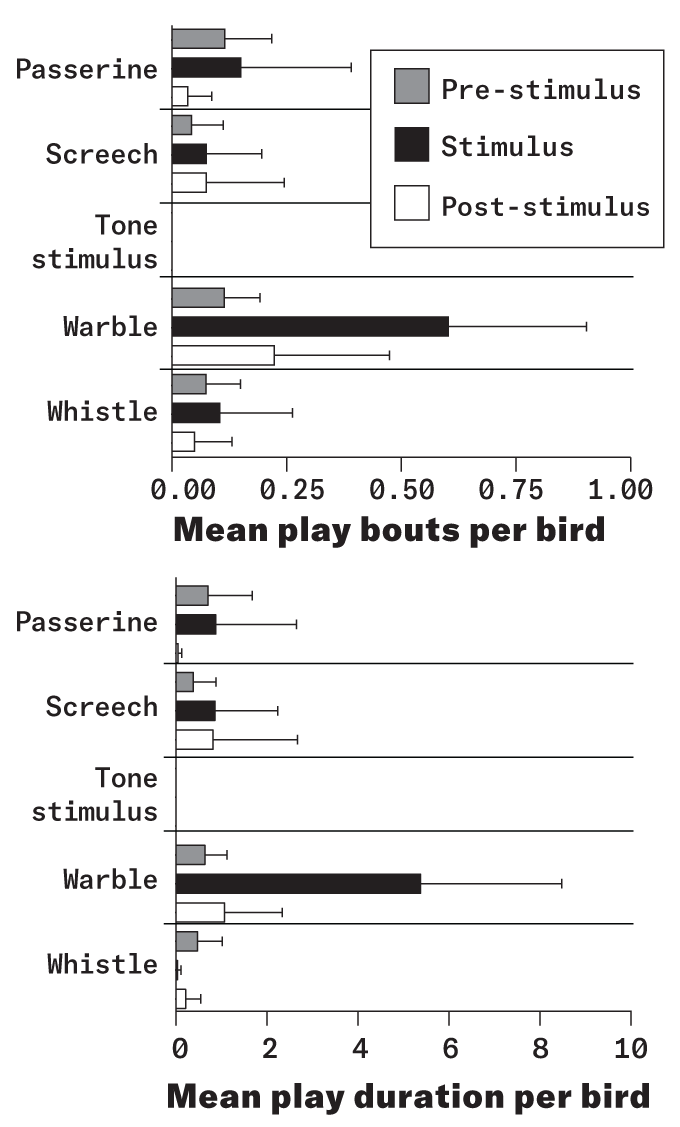

If scientists had better tools to measure positive emotions they’d be equipped to more deeply investigate the causes of happiness and how animals communicate it, with major implications for mental health among captive animals.

This need has inspired an audacious group effort to try to develop a “joy-o-meter” — or more likely, a set of happiness metrics — that could be used to better understand many critters, whether they are wild or captive, whether they walk, fly or swim.

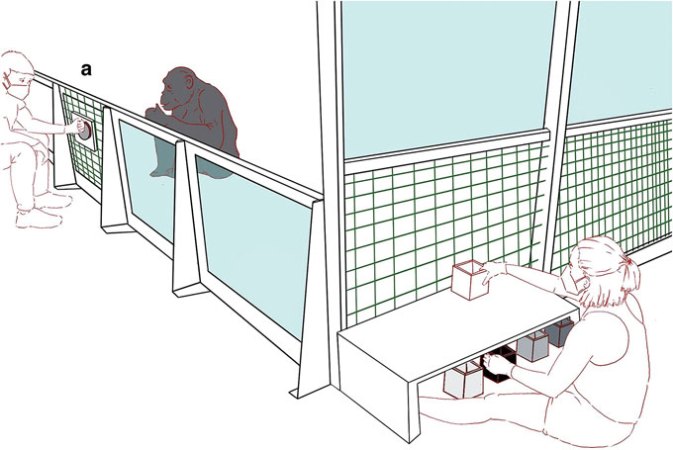

“The overall goal of the project is to establish this serious, scientific approach to positive emotion in animals, which has been hugely overlooked,” says Erica Cartmill, a member of the group and a cognitive scientist at Indiana University Bloomington. Cartmill studies great apes, but she knew that they wouldn’t be enough to build a universal metric. So she joined up with investigators with interest in studying positive affect in dolphins and parrots.

Their work is part of a much-needed surge of interest in studying animal emotions, says Marc Bekoff, an ethologist and emeritus professor at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies canine play behavior. “For a long time, people wondered whether dogs and other nonhuman mammals experienced positive behaviors like happiness and joy, and of course they do.” But, he adds, it is most likely different from human emotions.

In the joy-o-meter project, challenges quickly arose. It’s not only tricky to measure happiness, it’s also dicey to predict what event might induce that joyful state. “Studying emotions is actually really hard,” says Colin Allen, a project lead and philosopher at the University of California, Santa Barbara who collaborates with Cartmill.

To keep it simple, Allen and his colleagues have focused on a strict definition of joy as an intense, brief, positive emotion triggered by some event, such as encountering a favorite food or a reunion with a friend. That kind of “woohoo!” moment seemed easier to assess than, say, ongoing mild contentment. Even with a strict definition, the researchers are contending with variations in joy triggers and responses from one animal to the next, including within the same species or group.

“You want to make sure that what you’re putting out there is based on reality, as opposed to just guessing what is happening in the animal’s mind,” says Heidi Lyn, a comparative psychologist at the University of South Alabama in Mobile who is a co-leader of the project and is in charge of the dolphin studies as well as some of the ape work.

These efforts by Lyn and colleagues are important, says Gordon M. Burghardt, a biopsychologist and emeritus professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He is not involved in the joy project, but has studied animal play for more than 40 years. In that work, Burghardt says, coming up with a definition with five criteria in 2004 made it possible to identify play in diverse creatures including mammals, birds, lizards, turtles, fish, octopuses and bumblebees.

“Positive affect is as much worthy of scientific study as studying pain and negative emotions,” Burghardt says. Not only might scientists figure out how to better the lives of captive animals, they might get some clues to human happiness, too. “What is it that makes a good life?” he asks. “Those are the topics that are most worthwhile for us.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.