- COLIN WEAVER David Adams

- November 25, 2025

- 11:15 am

- No Comments

In an article published on Religion News Service, COLIN WEAVER, a postdoctoral teaching fellow at the University of Chicago Divinity School, says that if you want cover for rolling back climate initiatives, few one-liners do as much work as calling them religious…

United States

Via RNS

In his speech to senior military leaders on 30th September, US Secretary of War Pete Hegseth took a well-worn page out of the climate skeptic’s playbook: He framed climate change research, policy and activism as a “religion.” More specifically, he declared there was “no more climate change worship” in the Department of War.

Hegseth has been calling concern with climate change a “religion” for a while. He’s far from alone. Lee Zeldin, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, announced a wave of sweeping environmental deregulations back in March, exclaiming, “we are driving a dagger through the heart of climate-change religion and ushering in America’s Golden Age.” (Zeldin likes the rhetoric.)

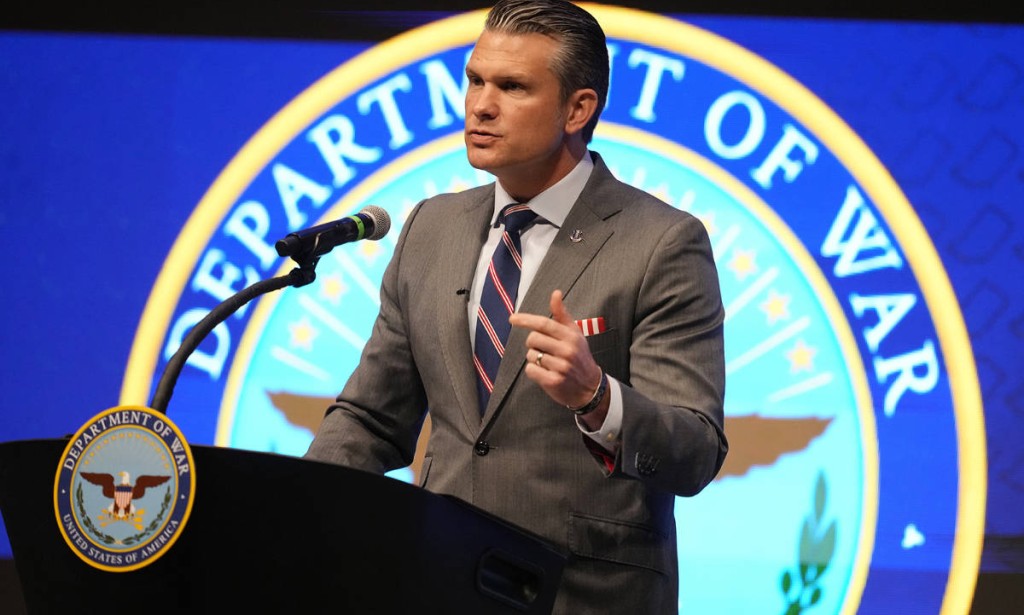

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth speaks during the 4th annual Northeast Indiana Defense Summit at Purdue University Fort Wayne, on Wednesday, 12th November, 2025, in Fort Wayne, Indiana. PICTURE: AP Photo/Darron Cummings.

Similar remarks were made during the first Trump administration. In 2016, Kathleen Hartnett White, a nominee to head the Council on Environmental Quality, called belief in climate change a “kind of paganism.” William Happer, a physicist and frequent adviser to President Donald Trump in 2017, called climate scientists “a glassy-eyed cult.” More recently, former Trump economic adviser and Heritage Foundation fellow Stephen Moore asserted that “climate change is not a science, it’s a religion.”

“The popularity of this rhetoric makes sense. If you want cover for rolling back climate initiatives, few one-liners do as much work as calling them religious.”

The popularity of this rhetoric makes sense. If you want cover for rolling back climate initiatives, few one-liners do as much work as calling them religious.

Anti-environmentalists and climate sceptics have been calling environmentalists “religious” and “fanatical” for decades. In 1971, Richard John Neuhaus published In Defense of People: Ecology and the Seduction of Radicalism, a book that described strands of the environmental movement as devotional, absolutist and under the delusion of a sacred mission.

Fast forward to 2003, when Michael Crichton – yes, that Michael Crichton – called environmentalism the religion “we all need to get rid of“. Two years later, Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe called “man-induced global warming…an article of religious faith.” (He’s the one who used the snowball to “disprove” climate change 10 years later.) Meanwhile, the Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation, a right-wing evangelical anti-environmentalist thinktank, has regularly used the same slogan.

In 2017, its “Resisting the Green Dragon” campaign went live, which called environmentalism a false religion. (On how American evangelicals pivoted from environmental curiosity in the 1980s to animosity in the ’90s, see Neall W Pogue’s The Nature of the Religious Right and Robin Veldman’s The Gospel of Climate Skepticism.) Likewise, throughout the 2000s and 2010s, journalists such as Bret Stephens and Congress-people like Lamar Smith invoked the climate-religion comparison.

We rely on our readers to fund Sight's work - become a financial supporter today!

For more information, head to our Subscriber's page.

But why does this rhetoric work? On one level, it is a familiar way to frame environmentalists as fanatical and dogmatic while positioning their critics as reasonable and realistic. After Zeldin mentioned climate religion, for example, he pivoted to discussing how his policies will save trillions in taxes, reignite American manufacturing and unleash “America’s full potential” while still protecting human and environmental health.

This sloganeering invites us to imagine anyone who wants to constrain our reliance on fossil fuels as opposed to a balanced approach to economics, energy and human well-being. From this angle, it just makes sense to drill, baby, drill and to roll back such principles as the endangerment finding, which states that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare.

Yet on another level, the idea of fighting a climate religion appeals to a narrative that has circulated widely among conservative evangelicals going back at least to the 1970s. In that story, secular humanists and others on the left have their own kind of religion, one bent on displacing Christianity. This narrative feeds what religion scholar Veldman calls the “embattled mentality” among many on the religious right. Drawing on her research among evangelicals in Georgia, Veldman argues that evangelical climate skepticism is significantly connected to how environmentalists and, more recently, climate advocates are associated with these forces of Christian displacement.

The idea of fighting a climate religion plays into these replacement anxieties. This dynamic is powerfully symbolized by evangelicals like Inhofe when they invoke their faith to counter climate science. For some right-wing Christians, the struggle against climate-based reforms is part of a larger holy war. That is something Hegseth, also an evangelical, makes explicit in “American Crusade,” which frames the US as besieged by secular leftists, including environmentalists.

You must be logged in to post a comment.